By Ilene Palacios

Exhibits

A & B: Javier Bardem & Alejandro González Iñárritu:

Javier Bardem is known as a Spanish

actor born in the Canary Islands, an autonomous community off the coast of

Africa that fell under Spanish rule starting from the early 1400s. “Los

canarios” are usually also considered to be racially Spanish, but Canarian

dialects are distinct from Peninsular Spanish. He was the first Spanish actor

to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role for his

part in Before Night Falls. He was

also the first to win for Best Supporting Actor, which he won for his haunting

role in the Cohen brothers’ adaptation of No

Country for Old Men in 2007.

Bardem got a second Best Actor

nomination this year for his role in Mexico City-born director Alejandro

González Iñárritu’s (a.k.a. “el Negro” for his dark skin) film Biutiful, nominated for Best Foreign

Language Film. Iñárritu was the first Mexican to be nominated for Best

Director. His four feature films have included a variety of languages, Spanish

above all, have been nominated for a dozen Oscars, and his first feature 2000’s

Amores Perros, was also nominated for

Best Foreign Language Film. His second most recent film Babel, was nominated for seven awards including Best Motion Picture

and Best Director.

Exhibits Aₐ

& Bₐ: Javier and Alejandro, Marked

Being

un-American/foreigners/Spanish-speakers, etc., there are a few ways, outside of

their work per se that Javier Bardem and Alejandro González Iñárritu have been

marked. Here are examples for each of them.

Aₐ In response to an article by the

Hollywood Reporter:

“Last September the Hollywood Reporter guessed as much when

it published a story titled “Whitest

Oscars in 10 years,” warning

everyone that no actors of color were being considered for this year’s top

prizes. This year’s awards does

include one person of color, Javier Bardem from Spain who starred in

“Biutiful.”…

Grammatical errors aside, this post

calls Javier Bardem a ‘person of color’ – which, being

Spanish/Canarian/European, he is not. It is difficult to tell here if the

writer was mapping his native language of Spanish onto his ‘color’ or race or

if his foreignness, his being not (White) American was to blame for this faux

pas.

Being

an actor that does work in both English and Spanish, Javier’s imperfect use of

English and his ‘natural’ use of Spanish is a source of anxiety for some. In

his interview after

winning Best Supporting Actor (for an American movie filmed in English) in 2007

one journalist starts off by saying to Bardem, “We want you to share some of

this joy…in English” and laughing.

If you are so

inclined to see that full interview:

Bₐ: Iñárritu, along with the two

other, according to the NY Times, of Mexico’s “most successful, acclaimed

directors” formed a sort of production conglomerate called Cha Cha Cha films.

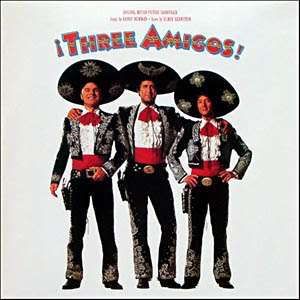

Hollywood has taken it upon itself to thus call this group “The Three Amigos”.

Ironically, this trio created the conglomerate to use its range of skills and

style as a point of leverage in Hollywood, i.e. for American-produced films.

Talk about a triple whammy of a culture and language suffering erasure, appropriation and mildly offensive iconization...and...hmm actually with that pose, I see the resemblance...

Marking

and Not Marking Films and People through the “Film in a Foreign Language” Oscar

Category

Awarding people and films based on a

particular set of U.S. standards that utilize somewhat arbitrary categories can

be limiting and perhaps problematic. Things can get even more muddled and

ambiguous when race, nationality and language come into play. I doubt many

people would claim that the various participants of the Academy Awards are

representative, be they various ethnic, racial and gender groups within the

U.S., people from countries around the world or speakers of different

languages. The Best Foreign Language Film category, created in 1956, seems to

aim to address race, nationality and language all in one, but it may be the

most limiting and inconsistent category of all, and they way it plays out seems

to be based on a number of intertwining inconsistencies, assumptions and folk

notions.

For instance:

1)

The category assumes (U.S.) English as the

Standard language for film

2)

The nominees for the category are chosen not

by language(s) but by country in/from which a film is produced (although many

American films nowadays are physically and artistically made [e.g. filmed,

edited] internationally)

3)

A country is allowed to pick only one film to

represent it, i.e. linguistically, which, coupled with events and notions of

the film, could lead to the film being an reference for iconization and fractal

recursivity related to the country’s people and erasure of dialects

and other language use in that country

4)

Even though a film can include multiple

languages and dialects of a language, as well as multiple countries in which it

is produced, usually one language in one form is chosen for the films

The Best Foreign Language Film

category seems not only to try to bear and pass down the burden or

representation of the entire world, but also to map and overlap nationality or

country with language together, and might even run the risk of dragging in

assumptions about ethnicity and race in with the mix. There are many points of fractal recursivity happening and it is

difficult to see at what point of difference the process began.

Iñárritu’s film Babel was nominated for Best Picture, not Best Foreign Language

Film, even though its director is Mexican and it contained Arabic, Spanish,

Japanese, a Japanese variety of Sign Language (in addition to English), because

it was an American-produced film. The

first film Javier Bardem was nominated for, Before

Night Falls, contained English, Spanish, Russian and French, but he was

nominated for Best Supporting Actor among other English-speaking actors, and

won. He also was nominated for Best Actor for Iñárritu’s Biutiful, a Foreign Language Film nominee.

This inconsistency and erasure that

occurs in this category come somewhat to light when the Best Foreign Language

Film nominees are presented at the Academy Awards show. This occurs in the form

of reading out the nominees’ film titles in English or the film’s own, “foreign” language:

Perhaps the actress couldn’t

pronounce those two film titles she read in English, or maybe it was how the

films were marketed. The actress reading out the nominees here reads the

nominees out, introducing them by saying, “From (insert country here)” instead

of “In (insert language here)”, and reads their titles are written on the

screen behind her. The Milk of Sorrow (in

Spanish, La teta asustada, literally

“the frightened breast”) and The White

Ribbon (in German, Das Weisse Band)

are read out in the language and country the film represents.

The White

Ribbon is

actually an Austrian-German production, but it represented Germany – and the

German language. The Milk of Sorrow

was produced by both Peru and Spain and contained both Spanish and Quechua, but

it only represented one country and one language, Peru and Spanish, respectively.

One Nation,

One Language, One People…One Category?

Based

on these examples, one might conclude the following about the Academy Awards

and its categorizations and conceptions about language and nationality (and

perhaps following that thread, race):

·

Actors’ ‘foreignness’

(I.e. they are ‘foreign-made’, ‘produced’ in another country) can mark them,

especially in relation to U.S. folk notions and ideologies about ‘normal’ or

‘appropriate’ language use, nationality and race in relation to English/American/White

·

Acting

whether done in English or another language, is thought of as more universal,

language-less – perhaps ironically; separate categorization for actors is not

necessary (because actors act like someone else anyway)

·

A film can

contain (a) “foreign” language(s)/actors/directors/filming/editing, but isn’t really considered as such unless it’s produced

in another country, and thus would require a separate category of nomination.

·

Language and

Nationality are almost interchangeable terms by which a film can be defined

·

The Academy

Awards’ (i.e. the U.S.) language ideology of one language/nation/people are imposed on Foreign Language nominees and assumes a similar language ideology applies for every country in the world; the nominated films must adhere to the Academy's rules and be the sole choice of one country with one language to represent that country -- this

has implications for what a film represents of a country’s people as being of a particular monolingual (i.e. one dialect too),

monoethnic, and perhaps monoracial essence

o

Perhaps in

line with the devaluation of Bilingualism in the U.S. and valuation of

“Standard English”?

o

Probably

erase other countries’ ideologies about language and its use and prevalence

·

A language

and a Country can be commodified and represented in a film

The only country that can be said to

predominantly speak English, Canada, was nominated for Best Foreign Language

Film for a film made in that country’s dialect of French. Never has a film from

Britain, Australia, New Zealand, etc. been nominated because mainly English is spoken there; they are

foreign countries, but they are English-speaking countries so they cannot qualify for this award though the award is given out to filmmakers of a country, not who are speakers of a language.

One might wonder what might happen if

Pakistan and India, which list English as an official language, ever submitted

an English-language film if it would nominated for the Best Foreign Language

Film Category. Would their foreignness and distance of geography, ethnicity and

race trump the similarity of language then? How much would such films need to fit

the ‘Foreign Language Film profile’, the U.S./Hollywood ideology about language, in order to even be considered for nomination?

Additional

References

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/26/movies/26roht.html?_r=1

No comments:

Post a Comment